Pitch decks and business plans tell the same story at different levels of depth. This article breaks down how each document functions and why aligning them accelerates credibility, momentum, and capital decisions

Dec 12, 2025, 12:00 AM

Written by:

Niko Ludwig

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways:

Match the moment. Use the deck to secure meetings and internal handoffs; use the plan when a counterparty is deciding to invest, lend, buy, or approve.

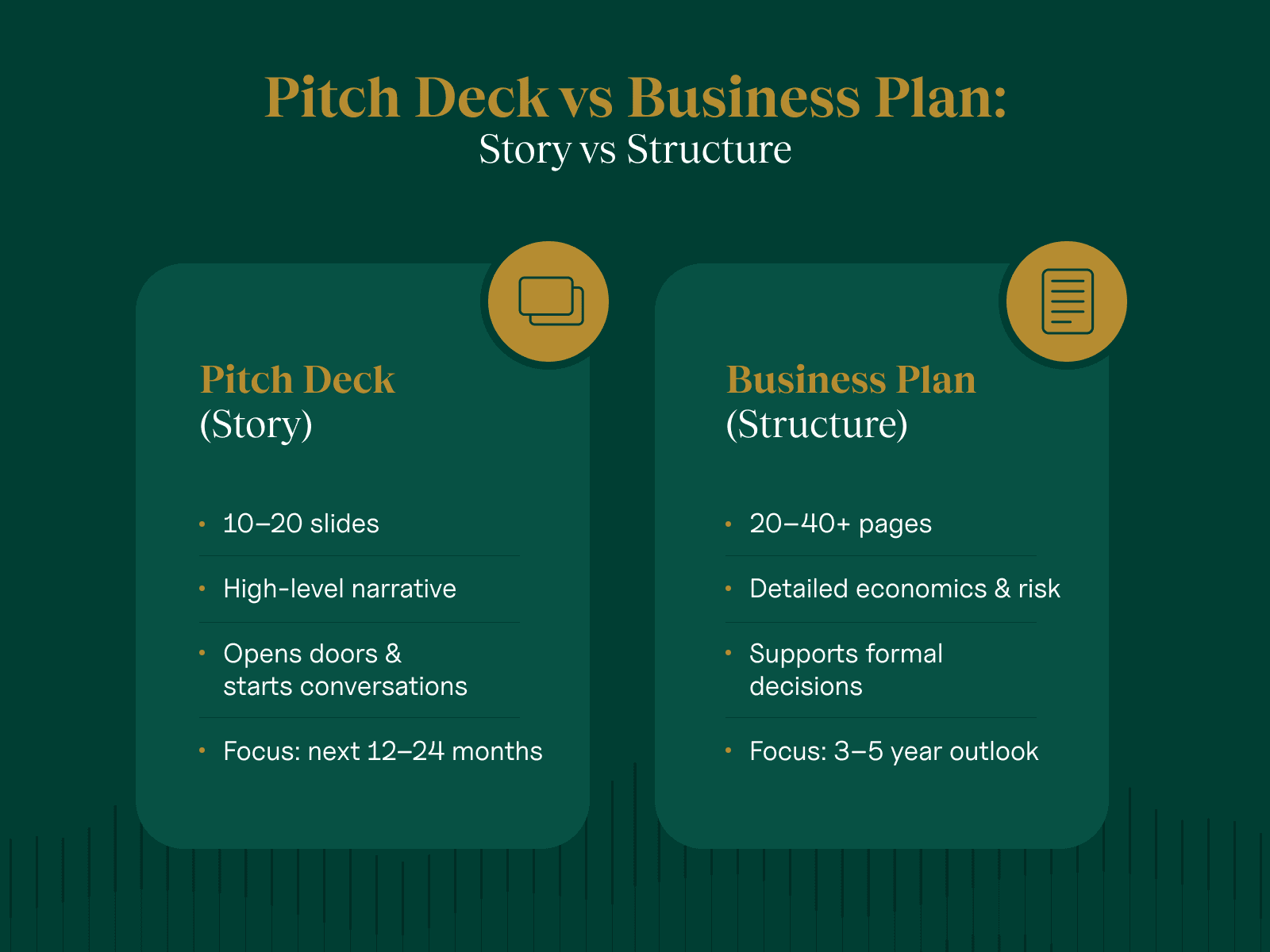

Same story, two depths. The deck compresses value creation into 10–20 scannable slides; the plan expands it into multi-year economics, risk, compliance, and operating discipline.

Consistency = credibility. Lock a single source of truth for AUM, revenue, margins, dates, and assumptions across deck, plan, and website. Misalignment is read as weak controls and slows (or ends) deals.

Operate a tight cadence. Refresh the deck before major outreach; update the plan annually or after strategic/regulatory changes.

Most firms already have a pitch deck on a shared drive and a business plan in an old PDF. What’s often less visible is how differently these documents function in real fundraising, partnership, or acquisition conversations. Investors, banks, and acquirers engage with each format in distinct ways, and understanding those differences strengthens how your story lands across audiences.

The real value lies in understanding how a pitch deck and a business plan work together, each highlighting different layers of the same story. They shape how fast conversations move, what kind of capital you attract, and how credible your firm looks next to competitors. The two documents tell versions of the same story, but they are built for different moments, different audiences, and different levels of scrutiny.

A useful way to think about pitch deck vs business plan is to start with context. The document you send should match the moment you are in, not just the asset you happen to have ready.

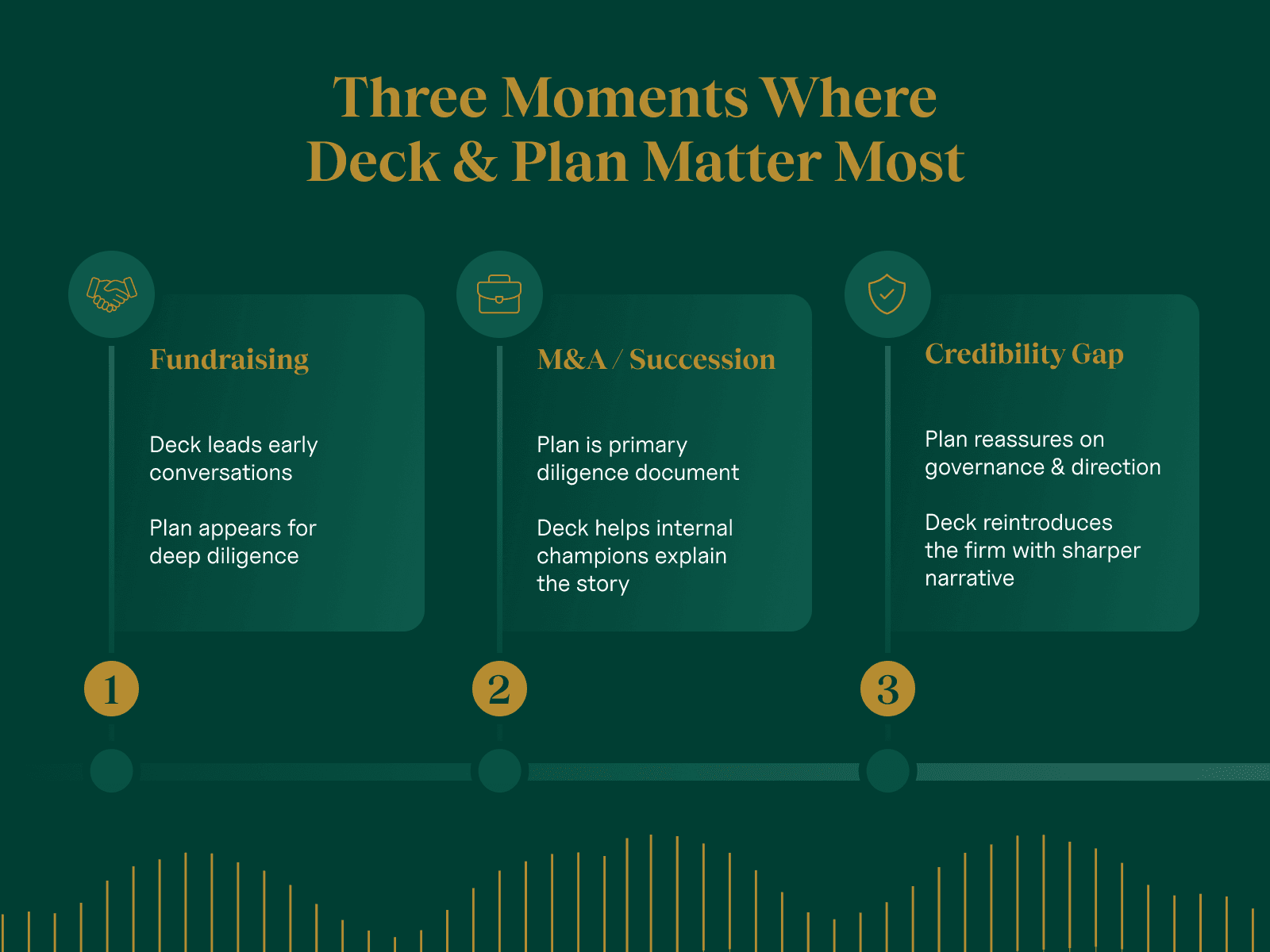

Three moments show up again and again:

The first is early-stage outreach. Early conversations almost always start with a pitch deck. It is the modern equivalent of walking into the room with a crisp story: who you serve, how you create value, and why now. A full business plan typically appears later, once a potential partner or decision-maker wants to understand the operating model, long-term sustainability, and underlying assumptions in more detail.

The second moment is formal evaluation or major partnership conversations. Organizations making significant commitments expect to see a robust business plan that covers ownership, client or customer segments, service or product mix, and operational risks. That aligns with how the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) and major lenders describe business plans: as a core artefact to assess risk, cash flow, and management quality when deciding whether to provide capital. A pitch deck still matters here because it helps your internal champions explain the high-level story to investment committees and boards, but the plan carries most of the weight in diligence.

The third moment is what you might call a credibility gap. Some firms come to market after a strategy change, a period of flat performance, or a public or reputational setback. In those cases, a well-structured business plan reassures stakeholders about governance and future direction, while a refreshed deck reintroduces the firm to partners and clients with a sharper, more confident narrative.

Before you start editing slides, it is worth asking a simple question: what decision am I asking the other side to make right now? If the decision is “Should we meet?” or “Should we introduce this firm to our committee?”, a pitch deck usually leads. If the decision is “Should we move forward, commit resources, or approve this initiative?” then a business plan (sometimes alongside a deck) becomes essential.

Through a business development and stakeholder-engagement lens, a pitch deck is a concise slide presentation, usually 10 to 20 slides, that compresses the key elements of your story. It is not a generic company overview. It is the short version of how you create value for a specific audience and how external support or collaboration accelerates that value creation.

A strong deck answers three questions quickly:

What need, gap or problem you solve

How your strategy and products address that problem

Why now is a relevant entry point for a new partner, supporter, or stakeholder

That clarity is exactly what makes the pitch deck vs business plan comparison meaningful. The deck condenses your story, while the plan develops it in depth.

The core purpose of a pitch deck is to open doors, not close deals. It starts conversations with potential partners, clients, collaborators, and decision-makers. It gives prospects a tool to explain your story inside their organisation, setting expectations for follow-up material. If you treat the deck as the final word instead of the entry ticket, you will either overload it or miss the depth many professional audiences expect.

Table-stakes content in a pitch deck is fairly consistent. You need:

A clear statement of the problem or market inefficiency

Your strategy and product set

Your distribution and client acquisition model

Your key performance metrics

Concrete proof points on credibility and operational reliability

If any of those elements are missing, investors will ask for them anyway, which usually means more meetings, more emails, and a slower process.

What a business plan means in a regulated, relationship-driven business

The phrase “business plan” often evokes a document written once for a bank loan and then forgotten. In modern organizational contexts, that view is outdated. A business plan is the structured explanation of how your firm intends to grow, serve, and protect its clients or customers within the operational, competitive, and compliance realities you operate in.

For service-based, advisory, technology, and professional organizations, a business plan goes deeper than a generic startup template. It should describe:

Your target client segments

Your fee structures and product architecture

The compliance or quality frameworks you operate under

How you intend to fund the firm and how ownership works

What succession looks like for partners and key leaders

A useful mental model is that the business plan is the internal and external governance document. Internally, it aligns partners and leadership on strategy, targets, and operational priorities. Externally, it gives buyers, partners, evaluators, and oversight bodies a structured way to evaluate whether your firm is sound, scalable, and well controlled. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and bank-side guidance both cast a thorough plan as central to raising capital and demonstrating viability.

When potential buyers review your plan, they are effectively asking three questions:

How do you manage client money and conflicts of interest?

How sustainable are your economics over several years?

Does your operating model match your promises?

If the plan is thin, outdated, or inconsistent with reality, sophisticated stakeholders assume your internal management is similarly weak. That is why the pitch deck vs business plan conversation cannot be separated from governance. More than marketing, it is a glimpse of how you run the firm.

Pitch deck vs business plan: key differences

At a high level, the differences between a pitch deck vs business plan are straightforward, but worth making explicit. Both tell the story of your firm, but in different ways, for different readers, and at different depths.

Format

Pitch deck: A slide presentation, usually 10 to 20 slides. Built for screens, meetings, and quick scanning, often with charts, headlines, and minimal text so a room can follow the story in real time. This mirrors how investors actually consume decks today.

Business plan: A longer text document or PDF, often 20 to 40 pages or more. Designed to be read (and re-read) in detail, with full paragraphs, tables, and appendices that people can mark up, circulate, and reference during formal reviews.

Purpose

Pitch deck: Create interest and secure meetings. Its job is to help someone decide “Yes, I want to learn more” or “Yes, I’ll put this in front of my committee.” It opens doors and accelerates early-stage conversations rather than answering every possible question.

Business plan: Supports full assessment and formal decisions. It is the document people use when they are deciding whether to lend, invest, or approve a transaction. It needs enough depth for a risk team, credit committee, or investment board to justify a “yes” to their own stakeholders.

Audience

Pitch deck: For VCs, PE funds, LPs, boards, key prospects. In practice, it is often shared with people who are seeing many opportunities in a short period of time and need to triage quickly. It also arms your internal champions with something they can show colleagues who will never meet you directly.

Business plan: For banks, regulators, buyers, institutional partners, boards. These audiences are accountable for capital, compliance, or integration risk. They use the plan to test assumptions, stress numbers, and understand the durability of your model beyond the next couple of quarters.

Level of detail and time horizon

Pitch deck: Includes narrative and key metrics, focused on the next 12 to 24 months: pipeline, AUM growth, unit economics, milestones. It highlights where you are today, where you’re going in the near term, and why now is a good entry point, without unpacking every operational detail.

Business plan: Includes a comprehensive strategy, operations, risk, and financials, often across a three- to five-year outlook. It shows how the business behaves over time: hiring, technology spend, regulatory obligations, margin progression, downside scenarios, and what happens if markets or growth assumptions change.

Update rhythm

Pitch deck: Refreshed before major capital raises, strategic reviews, or sales pushes. It evolves with your current story. As you gain traction, revise your positioning, and update your metrics accordingly.

Business plan: Updated at least annually or around major strategic shifts. It moves more slowly, but each update should reflect real decisions: new markets, new products, acquisitions, ownership changes, or a different funding strategy. A serious counterparty will expect those shifts to show up here, not just in the slides.

Common mistakes when choosing pitch deck vs business plan

When firms make pitch deck vs business plan decisions on autopilot, the same mistakes tend to show up.

1. Decks that look great but say very little

Some pitch decks:

Look polished and on-brand

Talk about vision, values, and “redefining wealth”

But barely mention performance metrics, customer traction, or operational controls

To an investor or potential partner, that kind of deck feels like a brochure, not an investment document. It’s all story, very little substance. That risk isn’t theoretical: in CB Insights’ analysis of startup failures, the most common reason founders gave for shutting down was “no market need”, cited in about 42% of post-mortems. In other words, teams often fall in love with a narrative that is unsupported by numbers. Design and branding help you get attention, but real metrics and clear controls are what turn an “interesting story” into a “credible, investment-worthy business.”

2. Business plans that hide the hard parts

On the other side, some business plans:

Bury churn or concentration risk deep in appendices

Mention regulatory or compliance issues only in passing

Gloss over what happens in tough markets

Experienced evaluators and investors are trained to hunt for bad news. If your plan makes it hard to find, they assume that there is more you’re not showing.

3. Copy-pasting generic startup templates into businesses that rely on service, expertise, or operational delivery

Another frequent issue is relying on generic startup templates that don’t reflect how the business actually works. The tell-tale signs:

Metrics focused only on headline growth (like signups or website traffic) with little explanation of how the organization actually delivers results

Funnels that ignore real-world steps such as onboarding, service delivery, approvals, or quality checks

No mention of the specific processes, standards, or operating practices that matter in your industry

When a deck or plan looks like it was lifted from a generic playbook, reviewers assume the organization hasn’t thought deeply about how it operates, or what it takes to scale responsibly.

4. Misaligned numbers across deck, plan, and website

A classic red flag:

One metric on the website says one thing

The pitch deck uses a slightly different figure

The business plan and data room show yet another version

Experienced investors notice this quickly. Misalignment doesn’t just look sloppy; it suggests weak reporting, which is exactly what institutional capital is paid to worry about.

A quick diagnostic for CMOs and growth leaders

To make this practical, you can use a short self-check. Ask:

Do we have a current pitch deck that reflects our latest AUM, economics, and strategy?

Do we have a current business plan that tells the same core story?

Are the key numbers (AUM, revenue, margins, headcount) consistent across deck, plan, website, and investor conversations?

Do we know which investors, banks, or partners expect a business plan before they can move forward?

If several answers are “no” or “not sure,” the priority is clear: you don’t need a brand-new framework. You need to update and align what you already have.

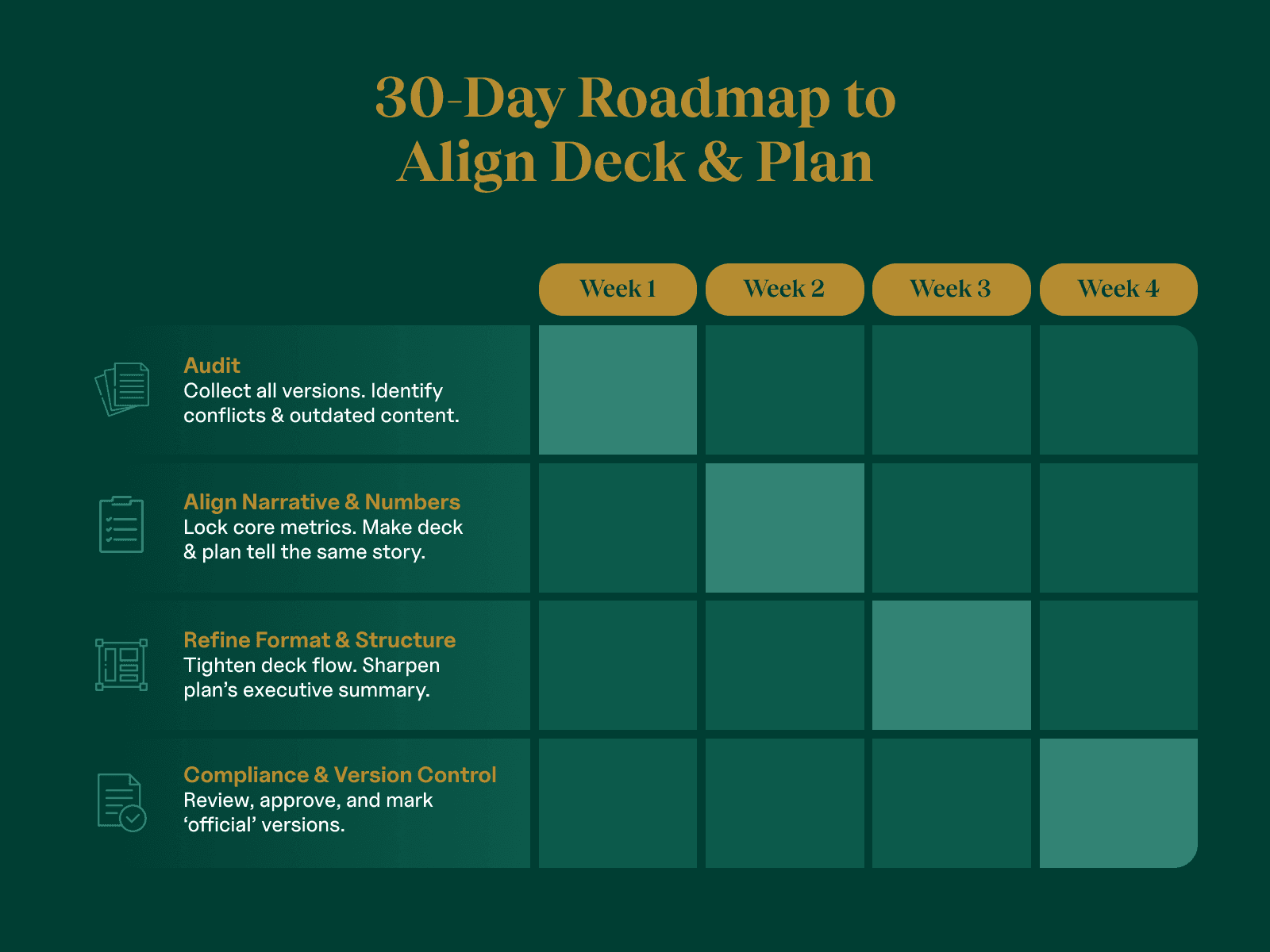

A simple 30-day roadmap to align deck and plan

You don’t have to fix everything at once. For most firms, a focused 30-day sprint is enough to get pitch deck vs business plan under control.

Week 1 – Audit

Collect all versions of: pitch decks, business plans, one-pagers, and any external-facing PDFs or summaries.

Make a note of conflicting metrics, outdated claims or positioning, slides or sections nobody uses anymore.

The goal: see the full picture, even if it’s messy.

Week 2 – Align narrative and numbers

Agree on a single set of core metrics with leadership and operational teams.

Decide: “These are the current metrics we stand behind”, “These are the assumptions we are comfortable publishing,” and “This is the version of our story we will consistently use.”Rewrite summaries and key slides so that the deck and plan tell the same core story, and ensure that numbers match across all stakeholder-facing documents.

Week 3 – Refine format and structure

For the pitch deck: Tighten slide order so that the story flows logically, and make sure each slide answers a clear question (“What do we offer?”, “Who is it for?”, “Why now?”)

For the business plan: Sharpen the executive summary (2–3 pages that a reviewer or potential partner can skim and actually understand). Add or clean up headings so readers can jump to sections on audience, model, operations, and long-term strategy.

Week 4 – Compliance, sign-off, and version control

Run both documents through compliance / legal review and get a quick check with one or two trusted external partners if possible.

Then: Mark “official” versions with dates and version numbers, store them in a clearly labelled location, and communicate internally: “If you’re sending anything to a potential partner, evaluator, or stakeholder, use these files.”

By the end of this process, you should be able to send your pitch deck and/or business plan to a serious counterparty without hesitation and without worrying what they might find if they compare one document to another.

Bottom line

The most effective firms do not treat “pitch deck vs business plan” as a theoretical debate or a one-time exercise. They treat both documents as living tools that support different stages of the same capital and growth journey.

The pitch deck opens doors. The business plan supports rigorous decisions. When both are current, aligned, and grounded in real numbers, you make it easier for investors, banks, and acquirers to say yes.

Frequently Asked Questions